GUIMark 2 is out now! View the new tests here.

Home | Detailed Analysis | Benchmark and Rendering Engine theory

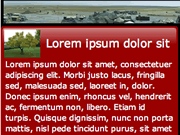

GUIMark is a benchmark test suite designed to compare the rendering systems of several popular UI runtimes. In general it should be able to give designers and developers a good indication of which technologies can draw complex interfaces at a smooth rate of motion. The test mostly addresses RIA technologies like Flash, Silverlight, HTML or Java, but was designed to be easily ported to any 2D GUI environment. The basis for this project was inspired by the Bubblemark animation test, but was designed to heavily saturate the rendering pipeline and determine what kind of visual complexity is achievable in the sub-60 fps realm.

The Test

The reference design was originally created in Flex and then ported to the technologies listed below. All results listed in the matrix as well as the detailed results page were run on the same Macbook Pro running Leopard for OS X, and running Win XP under a Boot Camp partition. Each test case was run 3 times in a new browser instance and the highest framerate observed was recorded. For the HTML test, the fastest performing browser on a each OS was used in the comparison matrix (Internet Explorer 7 and Safari 3 won for their respective OSes). All subsequent plugin based tests for the OS were tested in those browsers.

The reference design was originally created in Flex and then ported to the technologies listed below. All results listed in the matrix as well as the detailed results page were run on the same Macbook Pro running Leopard for OS X, and running Win XP under a Boot Camp partition. Each test case was run 3 times in a new browser instance and the highest framerate observed was recorded. For the HTML test, the fastest performing browser on a each OS was used in the comparison matrix (Internet Explorer 7 and Safari 3 won for their respective OSes). All subsequent plugin based tests for the OS were tested in those browsers.

My hope is to port the benchmark to all the other untested technologies listed below and I fully welcome any optimizations or ports that readers want to contribute. I’m really curious to see if any community experts or platform engineers are able to speed up their technology of choice. Although the code is fairly simple at a glance, there are no easy optimization paths to be found (and no cheating by turning off anti-aliasing).

Results

Results for Win XP running on Macbook Pro Intel Core 2 Duo 2.33 GHz

| Tech Base | Version | Average FPS | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browser | HTML | 28.36 / IE 7 | Download |

| SVG | - | - | |

| Canvas | - | - | |

| Flash | Flex 3 | 46.08 | Download |

| Flash 9 | - | - | |

| Java | Java 5 Swing | 19.37 | Download |

| Java 6 Swing | - | - | |

| Processing | - | - | |

| JavaFX | - | - | |

| Silverlight | Silverlight 1 / Javascript | 9.12 | Download |

| Silverlight 2 Beta / C# | 7.95 | Download |

Results for OS X 10.5 running on Macbook Pro Intel Core 2 Duo 2.33 GHz

| Tech Base | Version | Average FPS | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browser | HTML | 18.20 / Safari 3 | Download |

| SVG | - | - | |

| Canvas | - | - | |

| Flash | Flex 3 | 8.01 | Download |

| Flash 9 | - | - | |

| Java | Java 5 Swing | 7.19 | Download |

| Java 6 Swing | - | - | |

| Processing | - | - | |

| JavaFX | - | - | |

| Silverlight | Silverlight 1 / Javascript | 5.25 | Download |

| Silverlight 2 Beta / C# | 5.38 | Download |

Findings

I’ve been surprised with the results so far between WinXP and OS X. On the same machine its very clear which vendors take more advantage of the underlying hardware. The results for the different plugin technologies aren’t too surprising since it’s regularly admitted that most companies spend their optimization time on Windows due to its larger install base. This argument doesn’t hold any water though when comparing html rendering on Safari/Mac against IE /Windows where there’s roughly a 1.6 : 1 advantage to the IE team. I can’t help but wonder if the core apis on the Mac platform are creating any unnecessary roadblocks. I’m also extremely surprised at the rendering speed that Flash is able to pull off on Windows. I developed this benchmark under OS X and after compiling the results I’m considered making the testcase more intensive since Flash is running so fast, but for now maybe the really poor Mac performance will give Adobe something to work on.

You can read more about rendering engine theory, the structure of the test case itself, and detailed analysis of the results on the sub pages within the site.

Updates

John Dowdell from Adobe brought up a valid point that plugin vendors are restricted by the browser environments they run in. This is true to an extent, but the limitations enforced on plugins don’t come into play with the GUIMark test. Browsers typically restrict the number of event loops available to a plugin which caps the framerate to around 40 – 50 fps. GUIMark doesn’t come anywhere close to hitting that limit on Mac. There are also no restrictions to the amount of cpu available to a plugin running within the browser which is why all of them peg the cpu to 100%. To illustrate the point, I created an AIR implementation of GUIMark and ran it on my Powerbook and here are the results I got. The Flash players rendering engine performs no differently outside the browser then it does inside the browser. Until plugins start bumping up against the event loop or Beam Sync restrictions, Adobe, Sun, and Microsoft don’t get a free pass for slow performance on Mac.